Housing and the cost of living

Posted: September 20, 2023 | Author: julesbirch | Filed under: Cost of living, Housing market, Private renting, Rents, Social housing |Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

Inflation is starting to fall at last but the chances are what you pay for your housing has gone up along with the cost of everything else.

But this week’s inflation figures got me thinking about what we really mean by ‘inflation’ and how rising prices work differently in different tenures.

For starters, it all depends on the measure you use. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the one in the Bank of England’s inflation mandate so it matters most to its decisions on whether to raise interest rates or not.

CPI inflation affects the Bank’s decisions on interest rates which in turn drives mortgage rates so it is good news that it fell to 6.7 per cent in the year to August. However, CPI does not include owner-occupiers’ housing costs and it is not the index favoured by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

If you’re not confused yet, on the ONS’s favoured measure of CPIH (which includes owner-occupier housing costs and council tax) inflation fell to 6.3 per cent in the year to August.

However, those costs are based on an estimate of the equivalent rents that owner-occupiers would be paying. There may be sound economic arguments for excluding rising asset values from the inflation calculation but rising house prices still mean rising housing costs for home owners that are ignored.

Old-style Retail Price Index (RPI) inflation – also falling but still considerably higher at 9.1 per cent – is the only measure that directly includes mortgage interest payments but is seen as less accurate than CPI and is no longer treated as on official statistic by the ONS. Despite that, RPI is still used to set price increases in some leases.

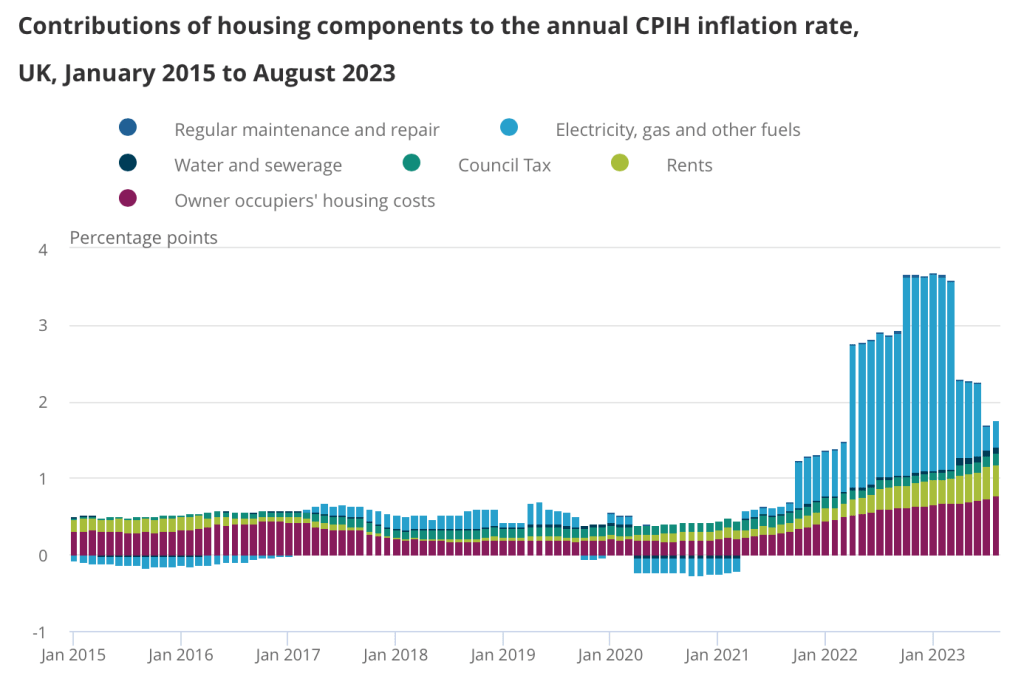

For all the differences between the three measures, it does seem clear that rising costs for renters and owners are playing an increasingly important role in inflation in household costs as the impact of the huge hikes in gas and electricity prices starts to recede. This ONS graph illustrates that only too clearly:

But what is really happening to house prices and rents? It all depends on who you believe.

So house prices are up by 0.6 per cent in the last 12 months, according to the ONS, or down by 4.6 per cent (Halifax) or down by 5.3 per cent (Nationwide). The difference is mostly down to time lags and the different ways in which they make up their indices but they present very different views of what’s happening.

Private rents rose by 5.5 per cent in the last year, according to the ONS, which sounds relatively modest compared to general inflation, but is the highest annual rate recorded since its Index of Private Rental Housing Prices began in 2011.

However, as this ONS graph showed earlier this year, indices produced by Zoopla, Rightmove and Homelet say private rents are rising at almost double that rate:

Time lags may be involved here too but the key difference is that the ONS figures are for all rents whereas the other three are for new lets only.

These numbers need to be treated with some caution since the ONS index is still billed as ‘experimental’ but the gap has continued through the year: rents for new lets are still rising at between 9.3 and 10.5 per cent a year.

Of course, most social rents rose by 7 per cent this year in England (slightly less in the other UK nations) but the key difference between social housing and the other two tenures is that the increase applies to all tenants not just new lets.

If those are the numbers on housing costs, how are they actually experienced by the people who pay them?

For home owners, house prices only reflect part of the price they pay for their housing, the starting point at the time of the initial purchase.

Beyond that it is interest rates that dictate monthly outgoings for those with mortgages. Rates in general have risen from 0.25 per cent in January 2022 to 5.25 per cent now driven by Bank of England concerns about inflation. Mortgage rates vary according to the size and nature of the loan but are down slightly since the chaos triggered by the Truss-Kwarteng Budget.

However, the term of the loan is also an important factor. The traditional 25-year mortgage is increasingly giving way to loans of 30, 35 and even 40 years.

The effect is to significantly reduce monthly outgoings – a £150,000 loan at 4 per cent interest costs around £165 a month less over 40 years than 25 – but dramatically increase the total amount of interest you’ll repay over the lifetime of the loan. Around £87,000 in interest over 25 years becomes £150,000 over 40.

And although lower monthly bills sound like they should be anti-inflationary, those more ‘affordable’ mortgage payments will likely mean house prices will be higher than they would have been otherwise.

To confuse the situation still further, most existing home owners do not have a mortgage to pay and house prices only come into play if they buy or sell.

For private renters, it’s all about the monthly rent – but the contrasting numbers suggest that existing renters who stay put are on average seeing much lower increases than those who move or take out a tenancy for the first time.

Some caution is needed here due to the experimental nature of the ONS index and its reliance on what landlords tell rent officers but the difference could indicate that landlords are less likely to raise rents for existing tenants and would rather have a steady income from their property rather than risk a void while they re-let it.

However, the thing that does not change is Local Housing Allowance (LHA), which has been frozen at what the government calls ‘enhanced rates’ since 2020. That’s bad enough for existing tenants but it leaves rents on new lets even more unaffordable.

Social tenants (and their landlords) can be grateful that the government abandoned plans to impose an LHA cap on their housing benefit but there is a striking contrast with private renters in how they experience rent increases.

The 7 per cent rent formula in England is a maximum but it applies to all tenants, not just new ones.

While social landlords may see it as a below-inflation increase, it is actually significantly higher than the increase paid by the average private renter.

Despite the crisis of unaffordable homes, the battle against ‘inflation’ has mostly been about prices for energy, fuel and food up to now.

Obscured by the way we measure inflation, the cost of living is always about the cost of housing too.