The state of the housing nation 2023

Posted: December 18, 2023 Filed under: Bedroom tax, Energy efficiency, Private renting, Tenants, Tenure change | Tags: English Housing Survey Leave a commentAs 2023 draws to a close, what is the state of the housing nation?

As always, the best place to start is the English Housing Survey, which has just published headline results for 2022/23. Here are five things that caught my attention.

1 The tenure and wealth gap

The results of the survey need to be treated with more caution than usual when comparing the results this year thanks to the impact of the pandemic, but the general trend on housing tenure is pretty clear.

Thanks in part to Help to Buy and other government schemes, the proportion of households who own their own home (64 per cent) has stabilised while the relentless growth of the private rented sector (18 per cent) has slowed. The social housing sector is still in slow decline but there is a significant difference between London (where it is home to 21 per cent of households) and England as a whole (16 per cent).

There were 874,000 recent first-time buyers in 2022/23 and they had an average (mean) deposit of just over £50,000.

Given that, it’s not surprising that family wealth has become increasingly important to people’s chances of buying. A growing proportion received help from family or friends (36 per cent, up from 27% in 2021/22 and 22 per cent in 2003/04) while 9 per cent used an inheritance for a deposit.

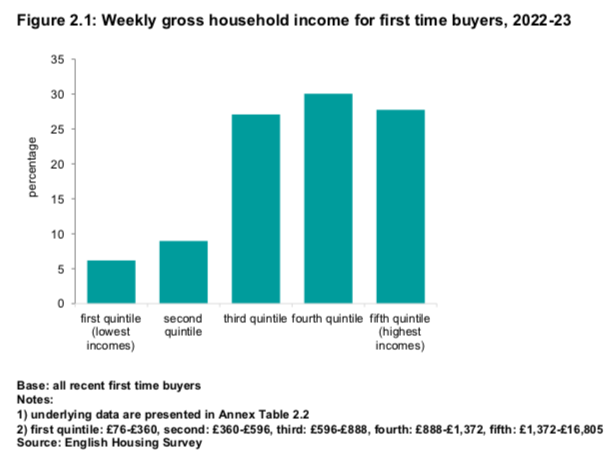

They were also higher earners: the majority of successful first-time buyers (58 per cent) came from the top two income quintiles and only a small minority (16 per cent) came from the bottom two.

A reshuffle that beggars belief

Posted: November 14, 2023 Filed under: Leasehold, Private renting | Tags: DLUHC, Rachel Maclean Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.

I’m not sure what Karl Marx would have made of the sixth housing minister in two years and the 16th in 13 years but it seems safe to say he would have run out of comparisons long ago.

The sacking of Rachel Maclean on Monday beggars belief not so much in itself – after nine months she was a relative veteran in the role – but in its timing.

Because the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) has not just one but two important pieces of legislation on its immediate agenda.

As she tweeted herself, she was due to start piloting the first of these, the Renters (Reform) Bill, through its committee stage in the House of Commons today (Tuesday).

The Bill delivers on the 2019 Conservative manifesto pledge of scrapping Section 21 and represents a delicate balancing act between the interests of landlords and tenants.

You might have thought, then, that it would benefit from a minister who knows her brief and is sufficiently across the detail to debate it with the opposition, both on the Labour side and among her own backbenchers. You might – but not Rishi Sunak.

Read the rest of this entry »A King’s Speech fit for a government running out of time

Posted: November 7, 2023 Filed under: Energy efficiency, Housebuilding, Leasehold, Private renting, Rough sleeping Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

The good news is that the King’s Speech does promise a Leasehold and Freehold Bill. The less good is that this is not yet the end, and maybe not the beginning of the end either, for the tenure that Michael Gove described as ‘indefensible in the 21st century’.

As first reported by the Sunday Times last month, leasehold reform will be part of the legislative programme for the next parliamentary session, confounding fears that it would be left in the pending tray until the next election.

But it will still be a race against time to get a complex piece of legislation through parliament in little over a year and its most far-reaching proposal is only a consultation for now.

The other major housing measure in the speech is confirmation that the government will continue with the Renters (Reform) Bill and abolition of Section 21 after introducing them in the last session.

There was no mention in the speech or the background documents of criminalising tents, despite home secretary Suella Braverman’s controversial comments about rough sleeping being a ‘lifestyle choice’.

Something like it could yet appear in the Criminal Justice Bill as the government looks to replace the Vagrancy Act but for the moment it looks as though the leak over the weekend was designed to kill the idea.

More surprisingly, neither the speech nor the background briefing document mention rules on nutrient neutrality that the government claims are blocking 100,000 new homes. An attempt to do this in the Levelling Up Act foundered in the House of Lords but ministers had vowed they would try again as soon as possible.

There is also a glaring contradiction between comments about the importance of energy efficiency in homes in the briefing on the Offshore Petroleum Licensing Bill and boasts about measures to support landlords by scrapping the requirement to bring their properties up to EPC C in the background to the Renters (Reform) Bill.

Read the rest of this entry »Housing confined to the fringes at Conservative conference

Posted: October 5, 2023 Filed under: Housebuilding, Leasehold, Private renting | Tags: Conservatives Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

It’s hard to know quite what to make of a Conservative conference at which housing was – quite literally – a fringe issue.

The only mention of housing in the prime minister’s speech was a reference to ‘thousands of homes for the next generation of home owners’ that will be built at the new Euston terminus of HS2.

Thousands of homes were already going to be built under the existing plan but that is now set to be ramped up under a Euston Development Corporation that seems all about maximising developer contributions from luxury flats rather than meeting local housing need.

Even levelling up secretary Michael Gove had little fresh to say about the H part of his portfolio from the main stage and made no reference to plans for renter and leasehold reform.

Read the rest of this entry »Net zero u-turn leaves tenants paying the bills

Posted: September 26, 2023 Filed under: Energy efficiency, Private renting Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

The clue is in Rishi Sunak’s language. This is about more than just his claim to be putting ‘the long-term interests of our country before the short-term political needs of the moment’ when he is doing the opposite.

Nor even his pledge to scrap a range of ‘worrying proposals’ on bins, flights and car-sharing that have never actually been proposed.

No, the obfuscation in his speech last week on net zero really becomes clear when you look at the details with the biggest implications for housing.

‘Under current plans, some property owners would’ve been forced to make expensive upgrades in just two years’ time,’ he said.

Some property owners? Who could he mean? The prime minister cannot bring himself to say private landlords because they simply do not fit in with his narrative of Westminster imposing ‘significant costs on working people especially those who are already struggling to make ends meet’.

Because his announcement actually does the complete opposite. The plan to tighten Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) for private rented homes would have saved millions of tenants £220 a year on average according to the government’s own impact assessment.

Read the rest of this entry »Is there a landlord exodus?

Posted: August 10, 2023 Filed under: Private renting Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

More pain for renters as landlords look to sell up. Renters compete with 20 others in battle to find a home.

Take even a casual glance at headlines about the dire state of the private rented sector and you come away with the impression that there is an exodus of landlords and that something, anything, must be done to persuade them to stay put.

The reality is more nuanced and confusing. While tenants are facing a shortage of properties to let and rapidly rising rents in many parts of the country, it is difficult to say why with any certainty.

Landlords face increased costs from rising mortgage rates, reduced tax reliefs and new requirements on the condition of their properties – even if it’s hard to remember them cutting their rents when interest rates fell close to zero after the financial crisis.

But the bigger picture is obscured both by a lack of reliable data and by claims that are either anecdotal or reek of self-interest.

Much of the data that does exist runs counter to the ‘landlord exodus’ narrative (so far, anyway, and there are time lags in the data). Government dwelling stock statistics estimate that the private rented sector grew by 123,000 homes between 2019 and 2022 but the sector has been pretty static since the middle of the last decade.

Read the rest of this entry »Wales consults on right to housing and fair rents

Posted: June 8, 2023 Filed under: Private renting, Rent control, Wales Leave a commentOriginally written as a column for Inside Housing.

The right to housing. Rent regulation. Two of the most prominent big ideas for fixing the housing system have just gone out for consultation in Wales.

There is still a long way to go after publication of what amounts to the lightest of green papers and there is a big difference between proposing something and implementing it. However, taken together they represent a big challenge to current orthodoxy.

The green paper on housing adequacy and fair rents is the result of the cooperation agreement between Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru. A white paper will follow but this is more of a call for evidence than a definite commitment to action or legislation.

The right to adequate housing is part of a United Nations covenant on economic, social and cultural rights that the UK signed up to almost 50 years ago. However, turning a vague aspiration to ‘housing as a human right’ into something more meaningful means incorporating it into national law, a move with strong support in the housing sector in Wales.

At the same time, as in the rest of the UK, support has been growing on the left and among private renters for some form of rent regulation.

Read the rest of this entry »